Home » Key Stage 3 English resources »

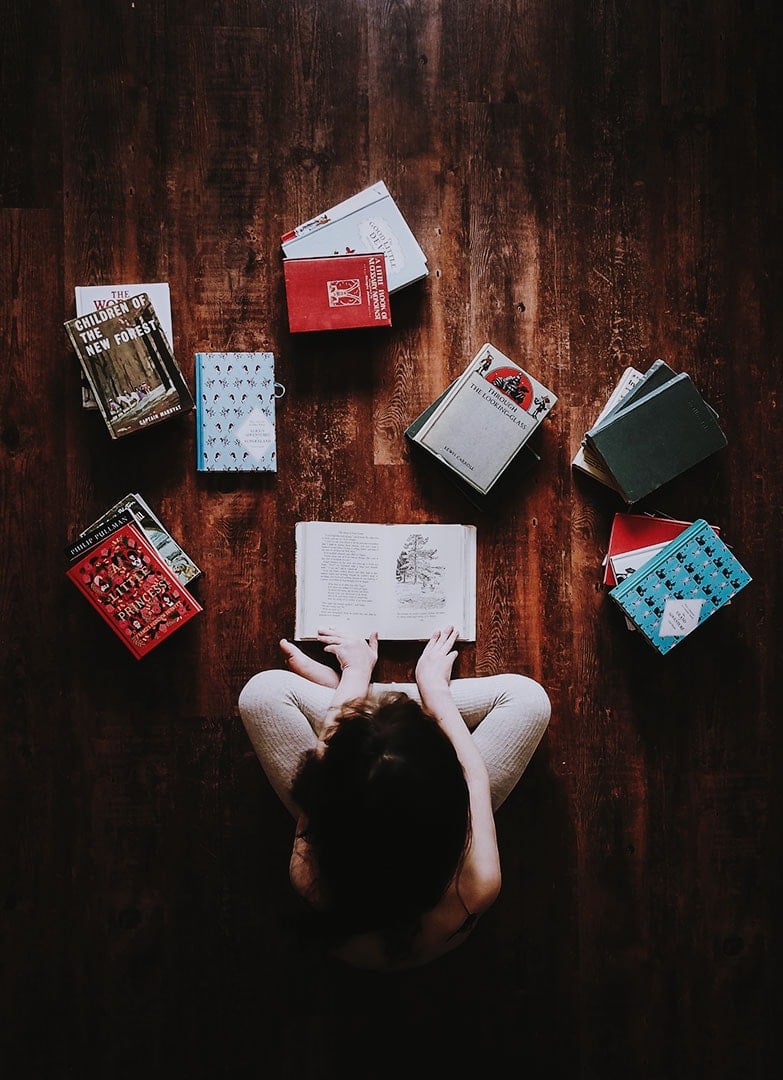

Common Entrance English revision books

- Common Entrance English Syllabus (Includes marks scheme)

- English Practice Exercises 13+: Common Entrance style practice questions (Practice Exercises at 13+). This one is particularly useful since it features a vast number of practice Common Entrance papers, and the answers (including the examiner marks schemes) can be found in this book.

- English for Common Entrance: Pupil’s Book– This is a useful practice aid, perhaps better for use throughout Years 7 & 8 rather than just revision.

- English ISEB Revision Guide: A Revision Guide for Common Entrance (ISEB Revision Guides)– A useful revision guide featuring model pupil answers, which although not always perfect, would achieve close to or actual A grades.

- A wider range of revision materials including suitable reading material for Paper 2 literature response questions can be found here. Here is a selection of suitable reading books for Year 8.

The comprehension paper

The non-fiction text

In this comprehension paper, the examiner is looking to test you on:

- Your vocabulary skills – do you know what the words mean and can you explain their meaning in a sentence?

- Your evidence skills. Can you prove your answer is correct by using a quote and explaining it?

- Your inference skills. This is when the answer isn’t in the text. Can you work out for yourself what the answer is, even if there isn’t a quote, and give a convincing reason?

- Can you comment on and discuss the style, language, and purpose? For example – why is the writer using an informal style? How does this affect how you read the piece? Why has the writer picked this word, or used these words and phrases twice? What is the point of this piece of writing – what is it trying to achieve – who is it aimed at?

- Can you provide answers which back up your opinions with solid evidence and create a convincing argument? When someone is charged with a crime, it is no use pointing a finger and claiming: “He did it!” You need solid grounds to put forward your point, provide the evidence (proof), in the form of a quote from the text, and finally, explain how your quote proves that your point is true. This process creates a convincing and believable answer.

- You need to be able to compare and contrast texts and explain your views clearly.

Reading the text

- Anticipate the questions. When you read through the passage or the poem, try to think what questions might come up. Pick out the words or phrases you think the examiner will have selected for questions. Try to spot which technical aspects of the piece will be explored in the higher mark questions. Then, by the time you reach the exam questions, you might have already worked out some of the answers.

- Scribble, underline and write notes all over the paper. Your parents have paid for the exam paper – so use it in any way which will be useful. If you spot words, phrases or quotes you think will be worth using later – highlight or ring them. Don’t be afraid to write notes on the question paper.

- How many answers are required? Read the marks scheme. If the question asks for three responses, and six marks are on offer, it is safe to assume that three reasons, each with one piece of evidence (a quote) and explanation are required. Use the marks details to work out how many reasons, and pieces of evidence and explanation you need to provide.

- Use the question to frame your answer. If the question asks “Explain how the poet uses rhythm to create a sense of tension”, begin your answer: “The poet uses rhythm to create a sense of tension by …” This approach focuses your answer and goes a long way to ensure your answer is relevant.

- The ‘what do you think’ and ‘why’ question. Normally there’s a 6-8 mark question asking for your views backed by reason and evidence (quotes). It’s often the last question on the paper. The marks scheme often tells the teacher to give marks for “any reasonable response”. Therefore so long as your answer is largely correct and convincing, it will gain marks. Why not answer this question first and guarantee marks from the start?

- Answer the questions in the best order for you. There’s no requirement to answer the questions in order, 1 ,2 ,3 etc. The examiner probably won’t mark them in order. Normally examiners mark all the questions 1s, then all the question 2s etc. If you think you might struggle to complete all the questions inside the time allowed, answer all the higher mark questions first. Answering question 8, followed by question 6, followed by question 4 is perfectly acceptable – just make sure you number your answers clearly! If you look at just the higher mark questions and add up the marks, these questions normally account for more than 50% of all the marks available. Therefore, if you answer these first, you are far more likely to pick up a pass mark than answering all the questions in order – especially if you miss out the highest mark question at the end due to not finishing the exam in time.

The unseen poem

All of the advice for the non-fiction comprehension above applies.

There are various language features you need to spot and comment upon in poetry analysis. An easy way to remember what might come up in a poetry comprehension is the mnemonic: “Sam’s Raptors” – Similes, alliteration, metaphors, symbolism, rhythm, assonance, personification, tone, onomatopoeia, rhyme, sarcasm. Perhaps write “Sam’s Raptors” down on your planning sheet to help you remember all the language features to watch out for.

Nearly all of the literary features will come up somewhere in the questions, or you will be expected to comment on examples of them when answering higher mark questions – particularly in the poetry section. Remember to use the term ‘stanza’ when describing poetry (not a paragraph, which is for prose), or ‘verse’ when the poem has a clear rhyming structure.

- For a good grade, you will need to be able to comment on the ‘metre’ and ‘rhyme’ (if applicable) of the poem.

- Metre: It’s worth revising these iambic, dactylic, trochaic and anapestic feet. There’s a good guide here. If you want to learn all the different metres, this book explains them in an easy to read format.

- Rhyme: be able to spot a clear rhyme scheme and describe it. There are some good examples here.

- Also, whether prose or poetry, consider the ‘audience’ – ie who the piece was written for – and how this affects how the piece has been written.

Figurative language / Imagery

- Alliteration – a series of words that begin with the same initial (starting) consonant sound. For example: “Peter Piper picked particularly prickly pickled peppers.” (All the words begin with a ‘p’ sound.) Also, there are specific terms for sounds produced by particular letters. A series of ‘Ss’ or “Shs” creates a hissing sound called “sibilance”. Any series of repeated consonant sounds is termed “consonance”, and in fact, alliteration is a special kind of consonance.

- Consonance is a term for when a consonant sound repeats anywhere in a series of words – for example, “all mammals named Sam are clammy.”

- Similarly, for vowels, the term is “assonance” – where a vowel sound is repeated anywhere in a series of words. For example: “Do you like blue?” said the ewe to the cow, who mooed. For an ‘A’ grade you need to know and understand these terms and point out examples of them in the text when answering questions.

- Metaphor – puts an image into the reader’s head by comparing one thing to another. For example, when describing a cricketer: “Rory is a demon bowler.” He isn’t really a demon, but it gives you an idea of what it’s like to face his bowling.

- Onomatopoeia (and yes, learn how to spell it!) – a word that sounds like the action it describes. For example – snap, crackle, pop; or plop.

- Personification – describing an object or animal as if it has human qualities. For example: “The wind whispered.” It didn’t really whisper – the wind doesn’t have lips or a mouth – but it gives the reader an idea of what the wind sounded like.

- Similes – puts an image into the reader’s head by comparing one thing to another, using ‘like’ or ‘as‘. For example: “She sang like an angel.”

- Hyperbole – An unbelievable exaggeration. For example “The cross country race went on for hundreds of miles.” This is clearly an exaggeration – unless you go to school in North Yorkshire in which case it is literal – ie true.

Avoid vague answers

Try to explain your answers with convincing reasons and arguments. Prove your point. Make the examiner believe you. For example: “This choice of words was really effective and I liked it,” doesn’t tell the examiner which words were effective, how and why they were effective; what image it placed in your head (and what type of figurative language was used) and exactly why you liked it. Remember to explain your points with evidence and argument.

The writing paper

The writing paper is 1 hour 20 minutes long and is – marked out of 50: two essays of 25 marks each.

Revision for the set book essay

Firstly, read the book – not as if it is a device of torture or a text more difficult to understand than a Sanskrit dictionary – but as if is was a paperback sunbed book with a bent spine found on holiday in Spain. Read it quickly. Skim. Then read it again. Try to enjoy it. If this is approach still sounds like something worse than death, buy the audiobook – either on CDs (amazon.co.uk is a good place to start) or download it from iTunes. Listen to someone reading the book to you over and over again. Failing that, if there’s a good film version available, which closely follows the book, watch that. Watching the film version first, or starting the first 100 pages by listening to the audiobook often helps you get into the book more quickly. Amazon and iTunes stock films on DVD, or you might get lucky searching on Youtube.

Here are some revision guides for popular set books:

- Lord of the Flies by William Golding. Sparknotes: here.

- Macbeth by Shakespeare. There’s an abridged film version here.

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck. A film version can be found here.

- Romeo and Juliet by Shakespeare. There’s an unabridged audiobook video here.

- The Merchant of Venice by Shakespeare. A complete audiobook is located here.

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

The essay questions – spot the different types of question

- Open-ended – a question that could be answered in a number of different ways. You need to pick the best genre for you in order to show off your writing skills. Your teacher will advise you.

- Descriptive – describing an event, scene, memory. Whatever you chose to write about, don’t write a story if the question asks for a description! Focus very specifically on exactly what the question asks for. Use figurative language (imagery) and powerful verbs to enhance your description. Frame your descriptions: perhaps describe a room from side to side or up and down. Or portray a landscape by looking at something in the foreground, then something further away, then focusing on something different close by – perhaps a character. Have a method for your description – avoid a random series of images. Here’s a useful revision guide for descriptive writing.

- Discursive – ie presenting both sides of the argument and reaching a conclusion. Really focus on answering the question. Here’s a useful guide to writing discursive essays.

- Persuasive – ie writing a convincing one-sided point of view. Use anecdotes, quotes, examples, original thought, and opinion and above all – explain your points to make them authoritative and believable. Use rhetorical questions, for example, a ‘surely sentence’. Here’s a guide on the differences between discursive and persuasive writing. Here’s a guide on how to argue effectively in formal writing.

- Personal writing – 1st person, for example, a recount or diary entry. Try to make the reader understand how you felt. Ensure your visual descriptions are vivid. Use figurative language (imagery) and powerful verbs to enhance your description of scenes, emotions, and characters. Here’s a revision guide for personal writing.

- Narrative – a story. Plan effectively. Ensure you have a structure. Perhaps use a three-act plan – a setting, a problem, and a resolution. Or start in the middle of the action (in media res) for something different and exciting. Above all know what you are going to write before you start writing. When describing, especially for scene-setting, use figurative language (imagery) and powerful verbs to enhance your use of language. Here’s a useful guide to narrative writing.

- Characterisation – show, rather than tell the reader your characters. Show how they move, talk, act, or react. Here’s some more advice about writing characters.

- With dialogue, make the attribution (he said/she said …) varied and interesting. Move it about – place it at the start, in the middle as well as at the end of speech sentences. If you are going to use speech, it’s essential to punctuate correctly. Here are some practise exercises for revision.

- Point of view – write from the point of view of a character you can relate to. A different or unusual point of view is a good thing – as long as it is believable. One student of mine wrote from the point of view of a dead fish once. Probably best avoided. However, a flashback story using points of view from the first day to the last day could be quite effective.

Planning techniques

Your school will have instructed you in many methods of planning essay tasks. These might include spider diagrams, mind maps, list plans etc. This book has some good study skills and planning techniques. This book offers some useful tips on Mind Mapping.

Or you might decide a very simple style of planning will work for you:

- Introduction (Refer to the question and briefly describe one or two points)

- Point one – Introduce the point – provide evidence (a quote, an example, or an anecdote) and explain how your evidence supports your point.

- Points two to eight – as above

- Conclusion – Refer back to the question, and reiterate (go over) your two or three best points with powerful evidence and explanation to back up your argument. Don’t introduce anything new to the conclusion. The conclusion might end up being a half-page paragraph.

- This free software may help with revision if you like this type of planning.

Remember – each new point should be written as a new paragraph. New point = New paragraph.

Which form of planning is the right one to use? Use whatever form of planning which works best for you. The aim of a plan is to ensure that you know exactly what you are going to write before you begin to write it.

Checking and editing your answers

According to the marks scheme, candidates need to: “demonstrate their ability to use correct spelling, punctuation, grammar, and syntax.” In other words, you need to be able to show that you can spell, write in proper sentences, use paragraphs and choose the most appropriate way to phrase your words. One way to help the examiner see that you care about the quality of your writing is to edit your work. Neatly cross out incorrect spellings and correct them. Put a clean line through a sentence or word you don’t like, and improve it. Neat crossings-out are good. They show that you can improve your work. They demonstrate that you are able to edit and correct spelling and grammar. Crossing out and improving work will improve your mark.

How can you revise for English?

A common question is “How can you revise for an English Exam”. Revise perhaps isn’t the right word. Think of it in terms of “How could I revise for a Tennis match?”

- You can prepare. Know everything which should happen, might happen, what difficulties could occur, what has occurred in the past, what is likely to occur, what isn’t likely to occur. Compare to how you might size up a Tennis match – What do I need to take with me? What is the court’s surface like? Weather: where’s the sun? What shots do I want to play if you have the opportunity? Are there any distractions at the side of the court – people, cars, errant pets? What do you know about your opponent? What are their strengths and weaknesses? How can you use your strengths to greatest effect at the same time as hiding your weaknesses from your opponent? How can I win, showing off my best ability? If you can think of answers to these questions, you know how to win that Tennis match. Are you still sure you can’t prepare for an English exam? Think about what you will be most comfortable writing with – an exploding fountain pen, a Biro which could engrave marks in stone, or a slightly safer rollerball? Do you need a drink midway through the exam? Will you have a choice as to where to sit? – avoid seats near doors, or next to open windows on cold days. Where there is a choice of essays, remember which type of question will result in your strongest answer.

- Handwriting. Of course, the hardworking examiner at your next school will take three times longer to mark your scruffy, hard to read, handwriting. Are you sure? Is it possible the examiner might look at a scruffy script and make a snap judgment that isn’t very good? If you are capable of neat handwriting, do you want to take that risk? Always write in your neatest handwriting.

- Every study skills book or revision guide will advise you to read the paper. Read it twice. Read it three times. “Read it,” underlined, perhaps in bold or even in italic. But how should you read it? Reading a comprehension text as if it includes instructions on how to save the world in the next 30 minutes or some other heightened form of life-threatening stress, is unlikely to allow you to fully understand what you are reading. Think about when you read and comprehend most successfully – perhaps when you read a novel quickly, or when you skim through your social media messages, or maybe when you blitz through ten new texts or emails? A relaxed attention to detail is required the first time you read the piece through. On the second or third reading, try to pre-empt the questions. Knowing what the examiner is likely to focus on, try to pick out words, phrases, and themes which you think you could be asked about. If you spy the word “mellifluous” it’s likely you’ll be asked about it.

- There is a list of useful Common Entrance revision books here